Geopoetics

There’s a neighbourhood in Athens called radio.

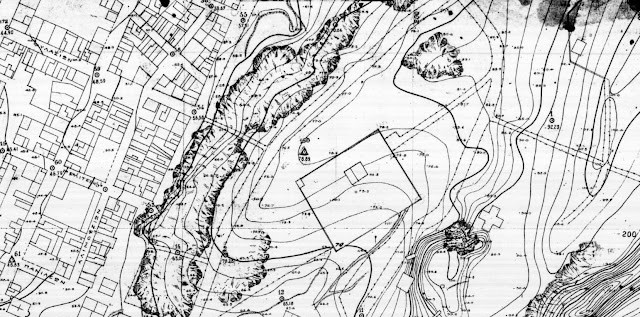

Ασύρματος – literally meaning “wireless” or “radio” – is a place named after an old naval radio school that used to sit on the slopes of one of the hills that float upwards into the Athens skyline. Today the neighbourhood is well hidden, built over and into the surrounding neighbourhood of Petralona. Immediately to the north, Thisseio, with its archaeological sites strewn about the place. Just over the hill to the east is the Acropolis. And not far to the south is a tangle of roads that untangle and race down to the sea.

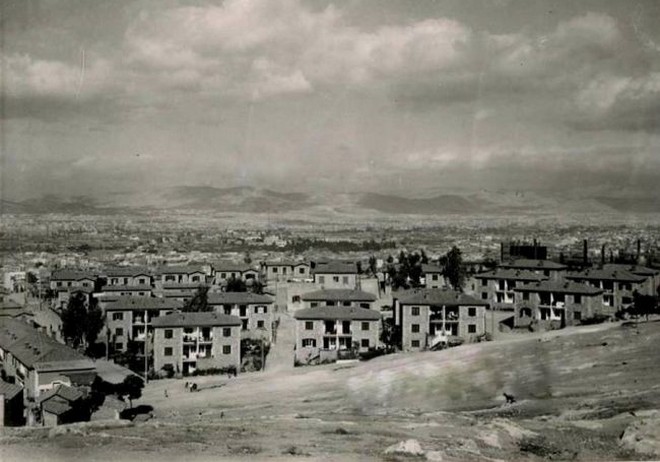

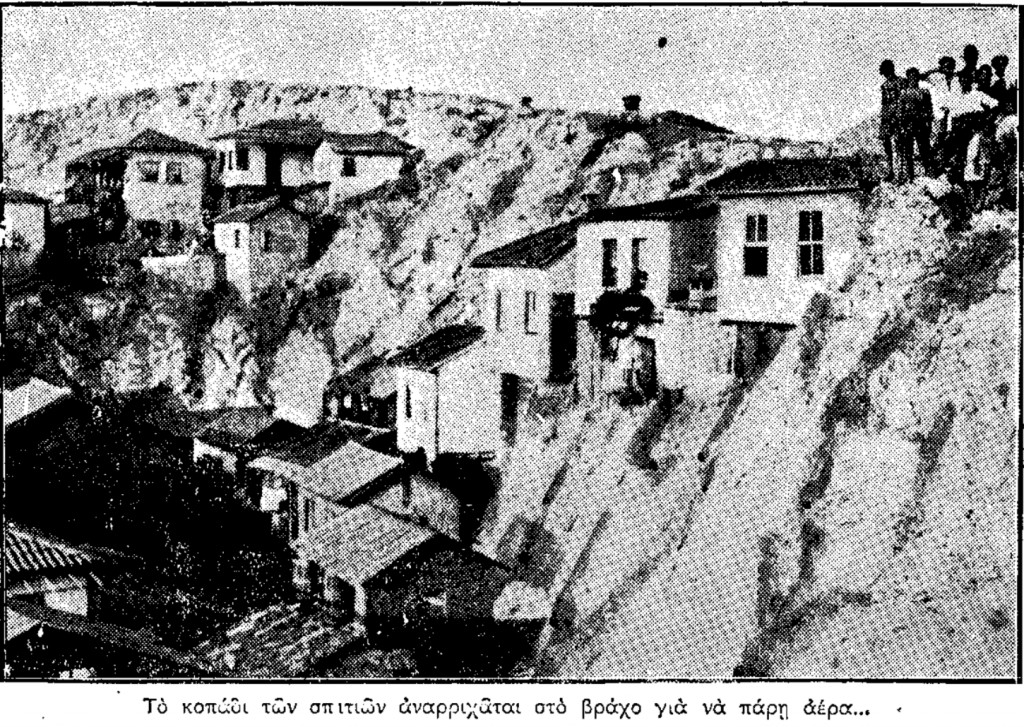

Asyrmatos, the neighbourhood called radio, is a place made out of displacement. It is one of the 1922 refugee settlements in the city. That year, the Great Fire of Smyrna, and what’s known as the Asia-Minor Catastrophe, triggered a chain of events that saw mass displacements across the Aegean and the population of Athens more than doubling. Three thousand people came to Asyrmatos as refugees, mostly from Antalya, a city on the southern coast of Turkey, and built the neighbourhood next to the radio school in what was then a quarry on the side of the hill. It’s in the middle of Athens, but it’s connected to the sea. You can see the waters of the Saronic gulf if you walk a short way up into the hill; and within the naval school was a radio antenna, tall enough to signal to the ships down by the port of Piraeus. The people who lived here held the Mediterranean with them. A neighbourhood called radio. Always broadcasting the sea.

The young Greek composer Nikos Skalkottas left Athens for Berlin in the same moment. Born into a working-class family on the island of Euboea in 1904, Skalkottas moved to Athens as a child, where his musical talents earned him free tuition at the Athens conservatory. His scholarships took him to Berlin, where he ended up studying composition with the great Arnold Schoenberg. Under Schoenberg’s tutelage, Skalkottas developed his compositional style using dodecaphonic – or twelve-note – techniques, centring on the use, repetition, and infinite circulation of all pitch classes.

Berlin at the time was jazz, cabaret, silent movies, ad hoc ensembles and musical opportunities. Skalkottas absorbed all of this, yet he also kept his musical imagination fixed on Greece, and began to develop ways of writing that incorporated his lessons from Schoenberg, the cosmopolitan modernity of Weimar culture, melodies of Greek musics, and invocations of the sea that surrounds them. His harmonic language was inclusive, mixing tonality with the dodecaphony of the avant-garde, finding freedom within the strict rules of serialism, playing with old forms and new textures. As Skalkottas himself wrote, his music sought a “sound coming from a new world, another sphere”.1

The word geopoetics extends from the word poeisis, meaning to make or to create. Geopoetics is to create geographies.

A century after people crossed the sea and built the neighbourhood called radio, some friends and I extended the sea-city relations held within this space. Working from Asyrmatos as a kind of jumping off point, we made a radio programme, produced in Athens and with sounds from other cities around the Eastern Mediterranean. The piece was conceived as a sound-cycle, an intercity symphony, a feedback loop; hearing Mediterranean relations and histories in counterpoint and circulation. We called it a Mediterradio. We sought to hear Athens as both transmitter and receiver, to turn the city into a sea and the sea into a radio.

The prompt for this work came from an invitation to be part of an art project: to build an Athens-based response to the centenary of the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses, with each of the book’s eighteen chapters being remapped from a different city. We were assigned the first chapter, “Telemachus”, with its themes of youth and emergence. At the outset of the novel, the protagonists are living in a Martello Tower on the coast just south of Dublin, and although the book is rightly known as one of the great texts of city writing, in these early pages it is also one of sea writing.

Ulysses was also published in 1922, the same year as the Fire of Smyrna, the Aegean displacement, the neighbourhood called radio. We sought to hold and hear those histories together, recreating urban space – as Joyce does – from memory and sound; thinking from the city to the sea and back again.

I spent a few months in Asyrmatos, immersed – reading, walking, listening, recording – and built a sound collage of the neighbourhood and the histories it carries. At the same time, we collectively made and gathered sound recordings from four cities around the sea – from Alexandria in Egypt, Nablus in Palestine, Damascus in Syria, and from Athens itself – cities that are all present in our Athenian community and in our Athens.

This was a collective composition. A sonic-spatial knowledge production. A set of wavelengths. Plenty of commonalities exist between spatial theory and sonic practice: both space and sound are inherently mobile and always in motion; both are intrinsically relational.2 And our sound-cycle became a plural text made up of different contributions, in which no one person has control of the whole story. Such is the Mediterranean. Always plural and multiple. A place of many textures and rhythms.

As well as these city sounds, and conversations we recorded around the neighbourhood, the music of Nikos Skalkottas was the main component of the piece. By 1933 Skalkottas was back in Athens. The Nazis had taken power and Schoenberg had left for America along with so many other Jewish artists and intellectuals. Skalkottas also left. Out of money and with his music now labelled “degenerate”, he returned to Greece where he suffered a nervous breakdown and had his passport confiscated for not having done his compulsory military service. He lived in Athens for the rest of his life, eking out a living as a back-desk violinist in the city’s orchestras, and transcribing folk songs for the newly established Centre for Asia Minor Studies.

Much of his late work was about the sea. In the years before his death in 1949, at the age of just 45, he composed a set of “Island Images” for piano (1943) and a full-length orchestral folk ballet called “The Sea” (1949). Musicologist Eva Mantzourani writes of Skalkottas’s compositions as a set of musical textures consisting not just of independent lines but a set of distinct and ever-shifting subtextures, creating what she calls a “polytextural fabric” that creates a topography of twelve-note sets that circle round one another.3 Music is texture just as sea is texture, always moving, layering and changing. Skalkottas’s music – as sea-writing, as topography – is also a kind of geopoetics.

In piecing these sounds together, our Mediterradio took on a kind of cartographic quality. Yet following ethnomusicologist Ana María Ochoa Gautier, this is less a practice of plotting sonic distances and marking audible territories, and more a process of making “an intellectual cartography that asks us to pay attention to the many possibilities of thinking in sound—one that is less a map and more a conglomeration of stories”.4 There are maps that you can hear but not always see. Sounds move, in constant feedback, bringing places closer together and amplifying commonalities that shuttle across histories and geographies. Sounds and stories bring together lives and struggles that are often understood separately. Athens is Damascus, is Nablus, is Alexandria, is Antalya. It is plenty of other places, too, not featured in our piece; is Beirut, is Jerusalem, is Istanbul, is Amman. In piecing these sounds and places together, we tried to make a geography, a sea-city.

Static

The Mediterranean is a space of compounding atrocities. Multiple forms of violence cluster and accumulate, themselves rooted in numerous ongoing colonialities. The places gathered in our Mediterradio speak of the dictatorial crimes of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, of occupation and apartheid (and worse) in Palestine, of authoritarian brutality in postrevolutionary Egypt, of pushbacks and border violence in Greece. These are places bound together in injustice. They are a set of interconnected unfreedoms.

I think of this as being about static. On one level, this means the weights and limits placed on people’s ability to move. Across these Mediterraneans, some are unable to leave and others are unable to return. Many have been forced out of their homes and cities, pushed off their land. Others wish to move but can’t. For others, even being mobile doesn’t mean becoming unstuck. Static means fixity: a denial of freedom of movement, or a form of movement with no freedom.

On another level, static is a sound – meaning interference, a block on communication, a technique of distancing. Static can be heard as an imperial sonority, gesturing towards the entanglements and mutual constitution of sound and empire – both on global scales and in ways that resonate around the Mediterranean. As music scholars have identified: “the emergences of European imperial orders […] have also been matters of the ear”.5

Sound cultures and sound technologies have long been used to impose discipline and order across the colonial divide: through militaristic violence, through the modulation of urban soundscapes, and through being a tuning device of imperial taxonomies. The world’s sounds and musics are placed in hierarchy. European sonorities and systems of harmony – along with the formulation of the European listening subject – continue to imagine their superiority, existing as the aural counterpart to Enlightenment notions of “reason” and “light”.6 Static, in this hearing, is the white noise of empire, the separation imposed upon cultures that are close together – sonically and otherwise – but are forced and considered apart.

Both kinds of static are a backdrop against which life takes place in Athens. The border follows people around. The colonial map weighs heavy, pressing down on people forced to move or unable to move or both. Greece is not a modern colonial power, but Greek border and citizenship policies reproduce imperial logics of racial hierarchisation. This plays out in urban space, where racialised policing intensifies, refugee populations are removed from the city, access to resources is limited for migrant communities, and politicians frame Athens as homogenous space to be protected and defended.

In November 2022, the (then) Greek Minister of Migration and Asylum, Notis Mitarakis, posed for cameras in a refugee camp just to the west of the centre of Athens. As he announced the camp’s closure – with the removal of residents to closed facilities far from the city – he stated that he was “returning the space to the Athenians”. In so doing, Mitarakis drew a border around who belongs in the city. The word “Athenians” becomes coded along ethnonational lines, conflating the city, its histories and urban spaces, with monocultural formations of ethnicity, language, and identity. And the result is an exclusion – literally and figuratively – of everyone else.

Yet the city is a gathering space of imaginations. Across multiple tempos – from the much-documented “migration crisis” (quote marks still necessary) of the last decade, to the much longer historical relations between Athens and its Mediterranean neighbours – communities produce space in the city that materialise seaward intimacies and complicate the city’s position in European civilisational narratives. Our Mediterradio is just one iteration of an ongoing set of creative projects coming out of a diverse and creative community; a collective that’s at once loose and tight, that is always looking to open possibilities for plural forms of belonging, and histories and futures based on these pluralities. The city is a song of struggles and solidarities. An amplifier of demands. A feedback loop of geographies invented and inscribed at street level.

What we heard in our Mediterradio was a set of sounds that hold people and places together, resonating in rhythms and melodies, in the commonalities and textures of lives lived out loud together. The piece was a counterpoint study of Mediterranean city sounds and the connections that carry between them: not in romanticised unity and unison, but still together, spilling into one another.

One bit of it is from a conversation on a bench in a small square in the neighbourhood. It was around Easter time in Greece, and the place was quiet yet also full of life, as families sat outside on yards and balconies sharing meals, with various musics drifting softly out and into one another.

My friend Kareem, who is from Damascus and also now from Athens, was telling me about how hearing particular sounds carries us to different times and places, and also how people carry sounds along migratory journeys, with the sea acting as a space of mixing (maybe remixing) geographies. These sonic practices are part of the ways that people make neighbourhoods, which are best understood through movement.

As Kareem put it, speaking as softly as the sounds that surrounded us: “Where we are now, they came from Antalya and from other places, and they mapped themselves in a place where they can see the sea. The sea is the common place. Many different neighbourhoods in the city have been built on this understanding – understanding the sea as the big city that really connects all of us. Here you will see how Athens gets more shiny and more lovely, with this contribution that comes to Athens: from Damascus where I come from, or from Palestine, or from Egypt. That’s what really makes it a diamond. When you understand the process of the neighbourhood, that’s the best position to really start to think about tomorrow”.

We aren’t the first people to think about these geographies and processes as sea-cities. In a book of Aegean Maps and Mapmakers, historian Spyros Asdrahas narrates the Aegean, its tumble of islands, as a “far-flung city”.7 The sea is a scattered urban complex. “A microcosm weaving a net of communications from one end to the other of the centreless sea-city”.8 The Aegean islands are dialogic landscapes, understanding themselves in relation and conversation. “Open and communicating societies”, as Asdrahas puts it.9 He details how communities of this sea-city exist in and through more-or-less constant movement and migration – all around the Mediterranean and between the islands themselves. “In 1673”, he writes, “15% of the population of Patmos bore names of local origin, and so on”.10 The same is true of placenames. The border is a fiction. Other cities from around the Mediterranean are also present in the Aegean sea-city; Asdrahas mentions Marseille and Alexandria, as well as Athens and Istanbul, Venice and Smyrna. All flow and are folded together. The sea-city is spatial continuity, gathering up all the edges.

Radio has long been associated with similar ideas. The early history of radio abounds with visions of a world united through sound. Rudolf Arnheim, in his radio treatise from 1933, called it “the great miracle of wireless”: “The omnipresence of what people are singing or saying anywhere, the overleaping of frontiers, the conquest of spatial isolation, the importation of culture on the waves of the ether”.11 And although radio is predominantly associated with national and colonial forms of sounding and listening, there is also a counterhistory of radio that is bound up with anticolonialism.

Within the great unmaking of imperial geographies and histories, and the reforging of cultural connections severed by colonisation, part of anticolonial praxis involved figuring out how sound technologies might generate alternate tactics of hearing and listening to the world. In the middle of the last century, radio stations transmitted and relayed and became anticolonial movements, broadcasting support for independence and liberation, and sounding out what Edwin Hill Jr calls a “new poetics of transnational and diasporic relating”.12 The medium played a central role in both colonial and anticolonial cultural politics: at once a relay point of imperial structures of governance and subject formation, and a space for developing intimacies and solidarities.

These are ongoing dynamics. Within the static, we still need to listen for the echoes of the “sound coming from a new world” that Skalkottas sought and that anticolonial movements made audible. Which reminds me of that line from Gramsci on how “the old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born”.13 Which reminds me of the interconnected unfreedoms of the Mediterranean, and how we’re all entangled in them and need new ways of listening to find new ways out.

Longing

At one moment as we were working on the project, my friends sat in a rocky nook in the hill overlooking the neighbourhood called radio and sang a Palestinian song to the sea. The song – “Haddi Ya Bahr Haddi” – is an exile song, sending greetings across the sea to the land, the olive trees, the mothers, and the birds. The sea is distance but it is also messenger, and in the space of both these things together it is longing. “Our voices are prevented from reaching each other”, Edward Said wrote, in a particularly poignant line in his portrait of Palestinian lives under conditions of colonisation and exile.14 Nablus, one of the cities in our quartet, is in the West Bank, where people are cut off from the sea.

This in itself – drawing on the aching and heartbreaking narration of the writer Suja Sawafta – is enough to grieve. Before we even think about everything else, it is enough to long for Palestine’s Mediterranean, where so many have ancestral homes and ties but now can only glimpse and hear the sea on occasion. Sawafta writes of being from near Nablus, and tells of her devotion to the city of Jaffa, where her family is from: “as if in a state of constant prayer. I lamented that I didn’t have the experience of my great-grandfather, who was fifty-three at the time of the Nakba and knew this land from the north to the south”.

“I mourned”, Sawafta continues, “that I didn’t know the city intimately, that I didn’t know where the locals went to eat, that I couldn’t make my coffee in a kitchen whose window overlooked the sea and had to buy an overpriced latté from a port-side café once every twelve years”.15

In this violence, and extending into exile across other borders too, song conveys and carries.

Although a very different situation, Asyrmatos is also full of longing. A place made of displacement. It seems now like an idyllic old Athens – a peaceful, almost picturesque place, nestled next to the hill and tucked away between busier streets, squares, and neighbourhoods. It is stone houses built after the war to replace the improvised refugee architecture. It is olive trees, bird song, an abandoned koutouki.16 It is the imperceptibility of memory: the radio school and antenna were burnt down as part of the events of Dekemvriana that tore through Athens in the winter of 1944, as one war ended and another one began, rendering the old name of the neighbourhood a confusion and an absence on the maps.

It is a 1961 neo-realistic movie called Συνοικία το ‘Ονειρο (or “The Dream District”), depicting hardship in the neighbourhood; a city of dirt streets and tin roofs, of people’s hopes seeking to ascend above the struggle of life in the refugee districts – depicting them to such a degree that Greek nationalists called the movie communist propaganda and the government tried to ban it. It is the song “Βρέχει στη Φτωχογειτονιά” (“It’s Raining in the Slums”) that soundtracks the movie, and became a kind of anthem to this side of the city’s identity. It is the miracle of walking through the underpass beneath the ringroad that circles the hill and finding yourself in another world entirely: a hallucination of olive trees and rocky expanse, blooming out onto the foot of Filopappou hill with its lexicon of graves, altars and demoi. It is the view of the sea that scatters your heart across a thousand possible places.

A neighbourhood called radio. A dream district. A place made out of displacement. Antennas that no longer exist. Struggle and dreaming to overcome it. My friends and I talked about the singers Fayrouz and Farid Al-Atrash, about the melodies of street markets, about sound and song and how they loop around the Mediterranean – how they constitute a set of sonic-spatial relations and imaginations. We talked about how the neighbourhood practices of those who moved from Antalya to Asyrmatos in 1922 are reflected in experiences of displacement and emplacement a century later.

Towards the end of his short life, Nikos Skalkottas was living almost entirely inside his own head. As his compositional style was out of step with the conservative trends and tastes of the Athenian musical establishment, performances of his pieces were few and money was thin. Undeterred, and seemingly in acceptance of his obscurity, he continued to compose for ideal ensembles that would never play his music and ideal audiences that would never hear it. During the years of the Nazi occupation of Athens he went hungry, and for a couple of months in summer 1944 he was imprisoned at an SS-run concentration camp of Haidari at the outskirts of the city, having been accused of being a member of the Greek resistance.

Skalkottas continued composing. Working on smuggled-in manuscript paper, he wrote a series of programmatic pieces that detailed the situation in the camp: a piece called “First of May” in tribute to some 200 people who were taken that day from Haidari to the execution grounds at Kaisariani; a piece called “Klouves” after the caged trucks that carried them there. These compositions were hidden in boxes in a storeroom, where they remained as Skalkottas was released and the occupation forces retreated, packing these manuscripts up and taking them back to Germany where they’d never be seen again.

As the city ignited into civil war, Skalkottas became ever-more detached. “Alone in the present”, Eva Mantzourani describes it, “and torn between the world of his past and an ideal imaginary future, where his music would be understood and appreciated, he harboured an intense nostalgic yearning to escape the reality of his Greek existence. But instead of acting, he withdrew in silence and lived the rest of his life in an inner exile”.17 His last piece, “Tender Melody”, exemplifies this longing. Containing multiple ostinati across the melody, harmony, and rhythm, “Tender Melody” has a circular, reiterative form. It is Skalkottas realising a free dodecaphony. The start of each phrase resolves the previous one yet in turn never resolves. The music is open ended, and as Mantzourani writes, “there is the impression that the piece could continue indefinitely”.18

It is music that could go on forever. It circles, achingly. Never still, never ending. In this it is again like the sea. Like the sea as it appears in the poems of Etel Adnan, whose sea-writing was another influence on our Mediterradio, and who writes longing as well as anyone. In Adnan’s sea poems, “currents circulate freely”, and “everything rolls and unrolls, runs and misses, weighs and crumbles, is circular and orbital”.19 Adnan’s sea and Skalkottas’s tenderness share forms and textures.

Across our sound-cycle, we sought to evoke something similar. A sea-city, circulating freely and eternally. I kept reading that opening chapter from Joyce’s Ulysses, and the way it uses the sea to set scenes for the city. Joyce’s writing is paradigmatic of what Teju Cole – another great author – calls “a kind of dense, epiphanic, city writing”.20 Wherein epiphany is not some dazzling, perhaps divine, instant of realisation, but is more a kind of urban experience based on the accumulation and rushing together of infinite thoughts and sensations. “Cities are made of multiplicity”, as Cole puts it.21 And epiphany is “the reassembly of the self through the senses […], an engagement with the things that quicken the heart”.22 Which only quickens further when you listen to multiple cities together, to the ways that people carry cities into other cities, and the ways we reassemble ourselves in the process.

Sound and song give us access to this epiphany. They narrate these movements and multiplicities, bringing us all into relation. They hold longing and hold memory, and open spatial imaginations that extend beyond the forms of detention and distance that themselves circulate and proliferate. Sonic imaginations are mobile (sound is always moving). They open ways of hearing space as open, also always moving. “You can’t hold places still,” as geographer Doreen Massey puts it. “What you can do is meet up with others, catch up with where another’s history has got to ‘now’, but where that ‘now’ […] is itself constituted by nothing more than—precisely—that meeting-up (again)”.23

All of this is audible. Sound, this meeting up again, this longing, this bringing many places together.

So when my friends sang to the sea – sang “Haddi Ya Bahr Haddi” – they did this work of meeting up again, of bringing places together. Of sonic-spatial imagination. Of circularity and circulation. Of epiphany and reassembly. Of topography and tenderness. Of longing.

Resistance

The piece closes with a conversation on refusing the current political vision of the sea. Refusing the current that pulls people into impossible lives and that ends life altogether. As a piece of sea-writing, our Mediterradio tunes into – and in turn seeks to become – a space of sonic creativity and connectivity in the face of colonial mappings, the violence of borders, and other forms of spatial injustice.

We imagine cities running into each other. Or seeing their reflections across a watery expanse. Athens is Nablus, is Damascus, is Alexandria, is Antalya. The colonial map turns the sea into a border, turns continents against one another. But the Mediterranean itself is a city, with all its geographies spilling over. By listening with mobilities, we aimed to hold together the multiple spatial imaginations that converge in a single place. A neighbourhood called radio. Listening from the city to the sea and back again.

In so doing, the Mediterradio seeks also to use sound as a form of spatial resistance. It narrates sonic strategies crafted from ways of being and knowing that exist in communities formed through migration and struggle. These are communities not defined by the border or the nation. Not ethno-states of listening and sounding, but spaces of counterpoint and circulation, of relation and transformation.

One of the sounds in the Damascus and the Athens recordings is that of arada – the traditional performance art of Damascus, made out of rhyme and rhythm, song and pun, call and response. The chants of arada resound with Damascene revolt against empires – against Ottoman imperialism and the French mandate – and they now regularly ring out into Athenian public space, usually with shoutouts to Syria and Damascus, to Palestine, and to Greece and Athens itself.

The revolutionary practice of cities singing for other cities – the chorus of rebellion that demanded the fall of regimes across the Arab world some 13 years ago – is stretched across the Mediterranean. Athens is enrolled in these insurgent geographies.

Yet these chants also find echoes in Athenian histories. During the Polytechneio uprising of November 1973, students occupied the Athens Polytechnic University as an act of collective resistance against the military dictatorship that had been running the country since 1967. The students framed this as an anti-imperialist struggle against U.S. support for the dictatorship – itself an extension of American interference in Greek politics since the Second World War and its violent repression of leftist movements.

On the streets outside the university, as well as the iconic chant for “bread, education, freedom”, there were chants for Salvador Allende, following the CIA-backed Pinochet coup in Chile two months earlier. And there were chants for Thailand. In October 1973, one month before Polytechneio, protestors in Bangkok occupied government buildings of the military junta – also backed by the U.S. The crowds at Polytechneio responded with the chant: “Tonight there will be Thailand”.24

People in Athens placed themselves into global anticolonial struggle. They voiced a kind of sonic Thirdworldism that moved in many directions at once. These things cut through the colonial taxonomies designed to divide our geographies and place us always at odds with each other.

They remind me of another line by Teju Cole, in another beautiful essay, “A Quartet for Edward Said” – the structure of which has inspired this piece. Cole writes: “difference is not about hierarchies but about the possibility of contrapuntal lines. Difference, at its best, interweaves and creates new harmonies”.25 Which I’ll tweak here to say that we can hear wavelengths not as separate channels or parallel lines, but as things that are also merging and emergent. Kareem says something similar about the Mediterranean in our piece: “This is something I believe we need to improve and work on. The sea is a one-channel radio between all the cities, and the city itself exchanges the sound”.

In this, the work of imagining the city as sea and the sea as radio is not so fanciful. The cities and sounds and the lives we share are multiple, interwoven, contrapuntal; and the wavelengths I’ve narrated here – geopoetics, static, longing, resistance – might permit us to hear and to be together, and to keep listening for those worlds we need beyond the horrors of the present one.

***This piece was written as a talk presented at the Royal Anthropological Institute on 9 April 2024***

- Nikos Skalkottas in Eva Mantzourani, The Life and Twelve-Note Music of Nikos Skalkottas. Ashgate, 2011: 246. ↩︎

- Georgina Born, Music, Sound and Space. Cambridge University Press, 2013: 20-24. ↩︎

- Mantzourani, The Life and Twelve-Note Music of Nikos Skalkottas, 148. ↩︎

- Ana María Ochoa Gautier, “Sonic Cartographies”, in Remapping Sound Studies, ed. Gavin Steingo and Jim Sykes. Duke University Press, 2019: 271. ↩︎

- Ronald Radano and Tejumola Olaniyan, “Hearing Empire—Imperial Listening”, in Audible Empire: Music, Global Politics, Critique, ed. Radano and Olaniyan. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016: 2. ↩︎

- Radano and Olaniyan, “Hearing Empire—Imperial Listening”, 8. ↩︎

- Spyros Asdrahas, “The Greek Archipelago—A Far-Flung City”, in Maps and Mapmakers of the Aegean, ed. Vasilis Sphyroeras, Anna Avramea, and Spyros Asdrahas. Oikos, 1985: 235-248. ↩︎

- Asdrahas, “The Greek Archipelago—A Far-Flung City”, 246. ↩︎

- Asdrahas, “The Greek Archipelago—A Far-Flung City”, 243. ↩︎

- Asdrahas, “The Greek Archipelago—A Far-Flung City”, 243. ↩︎

- Rudolf Arnheim, Radio. Faber and Faber, 1933: 14. ↩︎

- Edwin Hill Jr, Black Soundscapes White Stages: The Meaning of Francophone Sound in the Black Atlantic. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013: 124. ↩︎

- Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Lawrence & Wishart, 2005. ↩︎

- Edward Said, After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives. Pantheon Books, 1986: 19. ↩︎

- Suja Sawafta, “Two Shores, One Sea: Longing for Palestine’s Mediterranean”. The Baffler, February 28, 2024 – https://thebaffler.com/latest/two-shores-one-sea-sawafta ↩︎

- A koutouki is a traditional underground neighbourhood venue for music and food. ↩︎

- Mantzourani, The Life and Twelve-Note Music of Nikos Skalkottas, 76. ↩︎

- Mantzourani, The Life and Twelve-Note Music of Nikos Skalkottas, 335. ↩︎

- Etel Adnan, Sea and Fog. Nightboat Books, 2012: 8, 50. ↩︎

- Teju Cole, Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time. University of Chicago Press, 2021: 180. ↩︎

- Cole, Black Paper, 185. ↩︎

- Cole, Black Paper, 191. ↩︎

- Doreen Massey, For Space. Sage, 2005: 125. ↩︎

- Kostis Kornetis, Children of the Dictatorship: Student Resistance, Cultural Politics and the ‘Long 1960s’ in Greece. Berghahn, 2015: 248-249; Sara Salem and Tom Western, “Anticolonial Antiphonies”. Social Text, forthcoming. ↩︎

- Cole, Black Paper, 74. ↩︎

Leave a comment